- Joined

- Jun 27, 2006

- Location

- Chicago, IL

Original release date: October 2, 2018 | Last revised: December 21, 2018

Systems Affected

Retail Payment Systems

Overview

This joint Technical Alert (TA) is the result of analytic efforts between the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), the Department of the Treasury (Treasury), and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). Working with U.S. government partners, DHS, Treasury, and FBI identified malware and other indicators of compromise (IOCs) used by the North Korean government in an Automated Teller Machine (ATM) cash-out scheme—referred to by the U.S. Government as “FASTCash.” The U.S. Government refers to malicious cyber activity by the North Korean government as HIDDEN COBRA. For more information on HIDDEN COBRA activity, visit HIDDEN COBRA - North Korean Malicious Cyber Activity | CISA.

FBI has high confidence that HIDDEN COBRA actors are using the IOCs listed in this report to maintain a presence on victims’ networks to enable network exploitation. DHS, FBI, and Treasury are distributing these IOCs to enable network defense and reduce exposure to North Korean government malicious cyber activity.

This TA also includes suggested response actions to the IOCs provided, recommended mitigation techniques, and information on reporting incidents. If users or administrators detect activity associated with the malware families associated with FASTCash, they should immediately flag it, report it to the DHS National Cybersecurity and Communications Integration Center (NCCIC) or the FBI Cyber Watch (CyWatch), and give it the highest priority for enhanced mitigation.

NCCIC conducted analysis on 10 malware samples related to this activity and produced a Malware Analysis Report (MAR). MAR-10201537, HIDDEN COBRA FASTCash-Related Malware, examines the tactics, techniques, and procedures observed in the malware. Visit the MAR-10201537 page for the report and associated IOCs.

Description

Since at least late 2016, HIDDEN COBRA actors have used FASTCash tactics to target banks in Africa and Asia. At the time of this TA’s publication, the U.S. Government has not confirmed any FASTCash incidents affecting institutions within the United States.

FASTCash schemes remotely compromise payment switch application servers within banks to facilitate fraudulent transactions. The U.S. Government assesses that HIDDEN COBRA actors will continue to use FASTCash tactics to target retail payment systems vulnerable to remote exploitation.

According to a trusted partner’s estimation, HIDDEN COBRA actors have stolen tens of millions of dollars. In one incident in 2017, HIDDEN COBRA actors enabled cash to be simultaneously withdrawn from ATMs located in over 30 different countries. In another incident in 2018, HIDDEN COBRA actors enabled cash to be simultaneously withdrawn from ATMs in 23 different countries.

HIDDEN COBRA actors target the retail payment system infrastructure within banks to enable fraudulent ATM cash withdrawals across national borders. HIDDEN COBRA actors have configured and deployed malware on compromised switch application servers in order to intercept and reply to financial request messages with fraudulent but legitimate-looking affirmative response messages. Although the infection vector is unknown, all of the compromised switch application servers were running unsupported IBM Advanced Interactive eXecutive (AIX) operating system versions beyond the end of their service pack support dates; there is no evidence HIDDEN COBRA actors successfully exploited the AIX operating system in these incidents.

HIDDEN COBRA actors exploited the targeted systems by using their knowledge of International Standards Organization (ISO) 8583—the standard for financial transaction messaging—and other tactics. HIDDEN COBRA actors most likely deployed ISO 8583 libraries on the targeted switch application servers. Malicious threat actors use these libraries to help interpret financial request messages and properly construct fraudulent financial response messages.

A review of log files showed HIDDEN COBRA actors making typos and actively correcting errors while configuring the targeted server for unauthorized activity. Based on analysis of the affected systems, analysts believe that malware—used by HIDDEN COBRA actors and explained in the Technical Details section below—inspected inbound financial request messages for specific primary account numbers (PANs). The malware generated fraudulent financial response messages only for the request messages that matched the expected PANs. Most accounts used to initiate the transactions had minimal account activity or zero balances.

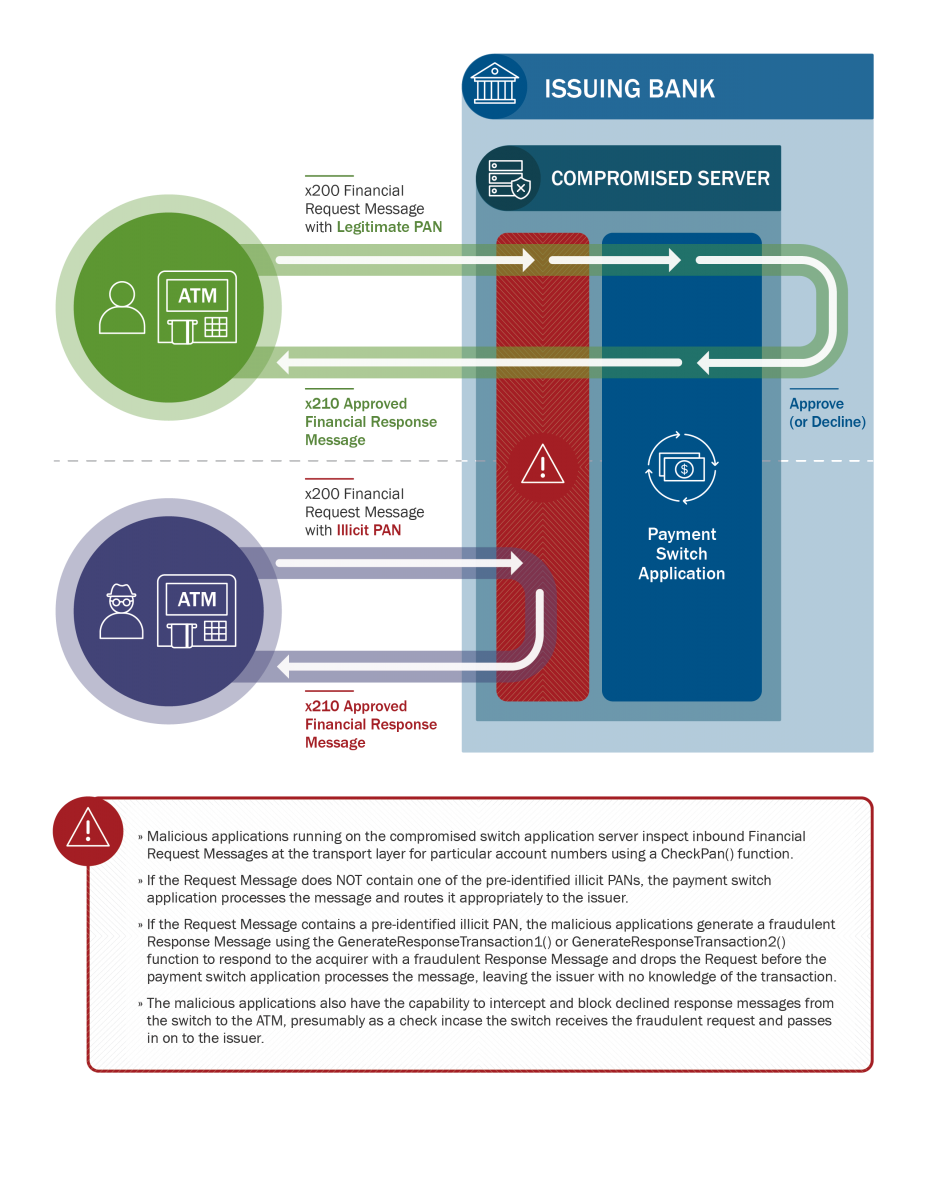

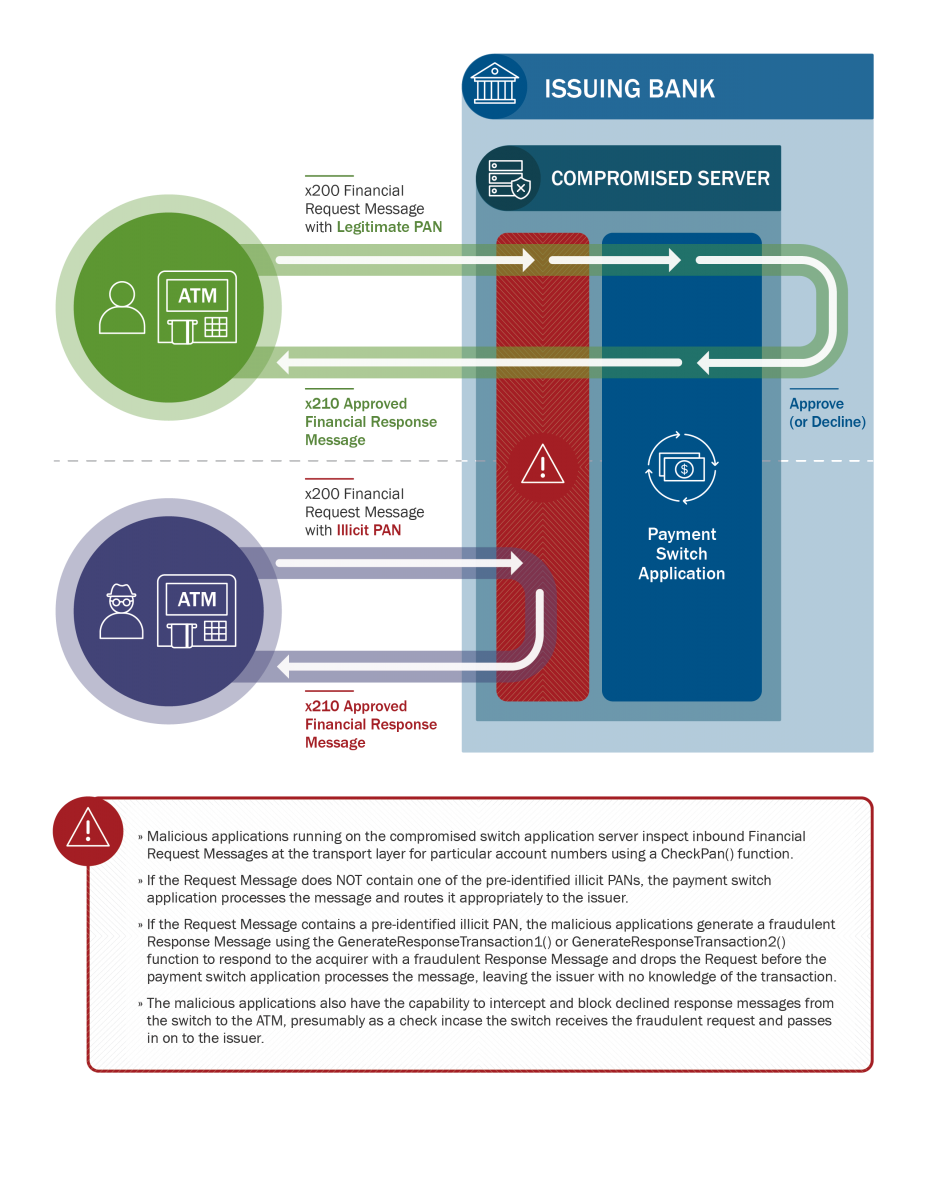

Analysts believe HIDDEN COBRA actors blocked transaction messages to stop denial messages from leaving the switch and used a GenerateResponse* function to approve the transactions. These response messages were likely sent for specific PANs matched using CheckPan()verification (see figure 1 for additional details on CheckPan()).

Technical Details

HIDDEN COBRA actors used malicious Windows executable applications, command-line utility applications, and other files in the FASTCash campaign to perform transactions and interact with financial systems, including the switch application server. The initial infection vector used to compromise victim networks is unknown; however, analysts surmise HIDDEN COBRA actors used spear-phishing emails in targeted attacks against bank employees. HIDDEN COBRA actors likely used Windows-based malware to explore a bank’s network to identify the payment switch application server. Although these threat actors used different malware in each known incident, static analysis of malware samples indicates similarities in malware capabilities and functionalities.

HIDDEN COBRA actors likely used legitimate credentials to move laterally through a bank’s network and to illicitly access the switch application server. This pattern suggests compromised systems within a bank’s network were used to access and compromise the targeted payment switch application server.

Upon successful compromise of a bank’s payment switch application server, HIDDEN COBRA actors likely injected malicious code into legitimate processes—using command-line utility applications on the payment switch application server—to enable fraudulent behavior by the system in response to what would otherwise be normal payment switch application server activity. NCCIC collaborated with Symantec cybersecurity researchers to provide additional context on existing analysis [1]. Malware samples analyzed included malicious AIX executable files intended for a proprietary UNIX operating system developed by IBM. The AIX executable files were designed to inject malicious code into a currently running process. Two of the AIX executable files are configured with an export function, which allows malicious applications to perform transactions on financial systems using the ISO 8583 standard. See MAR-10201537 for details on the files used. Figure 1 depicts the pattern of fraudulent behavior.

During analysis of log files associated with known FASTCash incidents, analysts identified the following commonalities:

Additionally, both commands use either the inject (mode 0) or eject (mode 1) argument with the following ISO 8583 libraries:

NCCIC recommends administrators review bash history logs of all users with root privileges. Administrators can find commands entered by users in the bash history logs; these would indicate the execution of malicious code on the switch application server. Administrators should log and monitor all commands.

The U.S. Government recommends that network administrators review MAR-10201537 for IOCs related to the HIDDEN COBRA FASTCash campaign, identify whether any of the provided IOCs fall within their organization’s network, and—if found—take necessary measures to remove the malware.

Impact

A successful network intrusion can have severe impacts, particularly if the compromise becomes public. Possible impacts to the affected organization include

Mitigation Recommendations for Institutions with Retail Payment Systems

Require Chip and Personal Identification Number Cryptogram Validation

Isolate Payment System Infrastructure

Logically Segregate Operating Environments

Encrypt Data in Transit

Monitor for Anomalous Behavior as Part of Layered Security

Recommendations for Organizations with ATM or Point-of-Sale Devices

NCCIC encourages users and administrators to use the following best practices to strengthen the security posture of their organization’s systems:

For additional information on malware incident prevention and handling, see the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Special Publication (SP) 800-83: Guide to Malware Incident Prevention and Handling for Desktops and Laptops.[2]

Response to Unauthorized Network Access

Contact DHS or your local FBI office immediately. To report an intrusion and request resources for incident response or technical assistance, contact NCCIC at ([email protected] or 888-282-0870), FBI through a local field office, or the FBI’s Cyber Division ([email protected] or 855-292-3937).

References

This product is provided subject to this Notification and this Privacy & Use policy.

Continue reading...

Systems Affected

Retail Payment Systems

Overview

This joint Technical Alert (TA) is the result of analytic efforts between the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), the Department of the Treasury (Treasury), and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). Working with U.S. government partners, DHS, Treasury, and FBI identified malware and other indicators of compromise (IOCs) used by the North Korean government in an Automated Teller Machine (ATM) cash-out scheme—referred to by the U.S. Government as “FASTCash.” The U.S. Government refers to malicious cyber activity by the North Korean government as HIDDEN COBRA. For more information on HIDDEN COBRA activity, visit HIDDEN COBRA - North Korean Malicious Cyber Activity | CISA.

FBI has high confidence that HIDDEN COBRA actors are using the IOCs listed in this report to maintain a presence on victims’ networks to enable network exploitation. DHS, FBI, and Treasury are distributing these IOCs to enable network defense and reduce exposure to North Korean government malicious cyber activity.

This TA also includes suggested response actions to the IOCs provided, recommended mitigation techniques, and information on reporting incidents. If users or administrators detect activity associated with the malware families associated with FASTCash, they should immediately flag it, report it to the DHS National Cybersecurity and Communications Integration Center (NCCIC) or the FBI Cyber Watch (CyWatch), and give it the highest priority for enhanced mitigation.

NCCIC conducted analysis on 10 malware samples related to this activity and produced a Malware Analysis Report (MAR). MAR-10201537, HIDDEN COBRA FASTCash-Related Malware, examines the tactics, techniques, and procedures observed in the malware. Visit the MAR-10201537 page for the report and associated IOCs.

Description

Since at least late 2016, HIDDEN COBRA actors have used FASTCash tactics to target banks in Africa and Asia. At the time of this TA’s publication, the U.S. Government has not confirmed any FASTCash incidents affecting institutions within the United States.

FASTCash schemes remotely compromise payment switch application servers within banks to facilitate fraudulent transactions. The U.S. Government assesses that HIDDEN COBRA actors will continue to use FASTCash tactics to target retail payment systems vulnerable to remote exploitation.

According to a trusted partner’s estimation, HIDDEN COBRA actors have stolen tens of millions of dollars. In one incident in 2017, HIDDEN COBRA actors enabled cash to be simultaneously withdrawn from ATMs located in over 30 different countries. In another incident in 2018, HIDDEN COBRA actors enabled cash to be simultaneously withdrawn from ATMs in 23 different countries.

HIDDEN COBRA actors target the retail payment system infrastructure within banks to enable fraudulent ATM cash withdrawals across national borders. HIDDEN COBRA actors have configured and deployed malware on compromised switch application servers in order to intercept and reply to financial request messages with fraudulent but legitimate-looking affirmative response messages. Although the infection vector is unknown, all of the compromised switch application servers were running unsupported IBM Advanced Interactive eXecutive (AIX) operating system versions beyond the end of their service pack support dates; there is no evidence HIDDEN COBRA actors successfully exploited the AIX operating system in these incidents.

HIDDEN COBRA actors exploited the targeted systems by using their knowledge of International Standards Organization (ISO) 8583—the standard for financial transaction messaging—and other tactics. HIDDEN COBRA actors most likely deployed ISO 8583 libraries on the targeted switch application servers. Malicious threat actors use these libraries to help interpret financial request messages and properly construct fraudulent financial response messages.

Figure 1: Anatomy of a FASTCash scheme

A review of log files showed HIDDEN COBRA actors making typos and actively correcting errors while configuring the targeted server for unauthorized activity. Based on analysis of the affected systems, analysts believe that malware—used by HIDDEN COBRA actors and explained in the Technical Details section below—inspected inbound financial request messages for specific primary account numbers (PANs). The malware generated fraudulent financial response messages only for the request messages that matched the expected PANs. Most accounts used to initiate the transactions had minimal account activity or zero balances.

Analysts believe HIDDEN COBRA actors blocked transaction messages to stop denial messages from leaving the switch and used a GenerateResponse* function to approve the transactions. These response messages were likely sent for specific PANs matched using CheckPan()verification (see figure 1 for additional details on CheckPan()).

Technical Details

HIDDEN COBRA actors used malicious Windows executable applications, command-line utility applications, and other files in the FASTCash campaign to perform transactions and interact with financial systems, including the switch application server. The initial infection vector used to compromise victim networks is unknown; however, analysts surmise HIDDEN COBRA actors used spear-phishing emails in targeted attacks against bank employees. HIDDEN COBRA actors likely used Windows-based malware to explore a bank’s network to identify the payment switch application server. Although these threat actors used different malware in each known incident, static analysis of malware samples indicates similarities in malware capabilities and functionalities.

HIDDEN COBRA actors likely used legitimate credentials to move laterally through a bank’s network and to illicitly access the switch application server. This pattern suggests compromised systems within a bank’s network were used to access and compromise the targeted payment switch application server.

Upon successful compromise of a bank’s payment switch application server, HIDDEN COBRA actors likely injected malicious code into legitimate processes—using command-line utility applications on the payment switch application server—to enable fraudulent behavior by the system in response to what would otherwise be normal payment switch application server activity. NCCIC collaborated with Symantec cybersecurity researchers to provide additional context on existing analysis [1]. Malware samples analyzed included malicious AIX executable files intended for a proprietary UNIX operating system developed by IBM. The AIX executable files were designed to inject malicious code into a currently running process. Two of the AIX executable files are configured with an export function, which allows malicious applications to perform transactions on financial systems using the ISO 8583 standard. See MAR-10201537 for details on the files used. Figure 1 depicts the pattern of fraudulent behavior.

During analysis of log files associated with known FASTCash incidents, analysts identified the following commonalities:

- Execution of .so (shared object) commands using the following pattern: /tmp/.ICE-unix/e <PID> /tmp.ICE-unix/<filename>m.so <argument>

- The process identifier, filename, and argument varied between targeted institutions. The tmp directory typically contains the X Window System session information.

- Execution of the .so command, which contained a similar, but slightly different, command: ./sun <PID>/tmp/.ICE-unix/engine.so <argument>

- The file is named sun and runs out of the /tmp/.ICE-unix directory.

Additionally, both commands use either the inject (mode 0) or eject (mode 1) argument with the following ISO 8583 libraries:

- m.so [with argument “0” or “1”]

- m1.so [with argument “0” or “1”]

- m2.so [with argument “0” or “1”]

- m3.so [with argument “0” or “1”]

NCCIC recommends administrators review bash history logs of all users with root privileges. Administrators can find commands entered by users in the bash history logs; these would indicate the execution of malicious code on the switch application server. Administrators should log and monitor all commands.

The U.S. Government recommends that network administrators review MAR-10201537 for IOCs related to the HIDDEN COBRA FASTCash campaign, identify whether any of the provided IOCs fall within their organization’s network, and—if found—take necessary measures to remove the malware.

Impact

A successful network intrusion can have severe impacts, particularly if the compromise becomes public. Possible impacts to the affected organization include

- Temporary or permanent loss of sensitive or proprietary information,

- Disruption to regular operations,

- Financial costs to restore systems and files, and

- Potential harm to an organization’s reputation.

Mitigation Recommendations for Institutions with Retail Payment Systems

Require Chip and Personal Identification Number Cryptogram Validation

- Implement chip and Personal Identification Number (PIN) requirements for debit cards.

- Validate card-generated authorization request cryptograms.

- Use issuer-generated authorization response cryptograms for response messages.

- Require card-generated authorization response cryptogram validation to verify legitimate response messages.

Isolate Payment System Infrastructure

- Require two-factor authentication before any user can access the switch application server.

- Verify that perimeter security controls prevent internet hosts from accessing the private network infrastructure servicing your payment switch application server.

- Verify that perimeter security controls prevent all hosts outside of authorized endpoints from accessing your system.

Logically Segregate Operating Environments

- Use firewalls to divide operating environments into enclaves.

- Use Access Control Lists (ACLs) to permit or deny specific traffic from flowing between those enclaves.

- Give special considerations to enclaves holding sensitive information (e.g., card management systems) from enclaves requiring internet connectivity (e.g., email).

Encrypt Data in Transit

- Secure all links to payment system engines with a certificate-based mechanism, such as mutual transport layer security, for all traffic external or internal to the organization.

- Limit the number of certificates used on the production server, and restrict access to those certificates.

Monitor for Anomalous Behavior as Part of Layered Security

- Configure the switch application server to log transactions. Routinely audit transactions and system logs.

- Develop a baseline of expected software, users, and logons. Monitor switch application servers for unusual software installations, updates, account changes, or other activity outside of expected behavior.

- Develop a baseline of expected transaction participants, amounts, frequency, and timing. Monitor and flag anomalous transactions for suspected fraudulent activity.

Recommendations for Organizations with ATM or Point-of-Sale Devices

- Implement chip and PIN requirements for debit cards.

- Require and verify message authentication codes on issuer financial request response messages.

- Perform authorization response cryptogram validation for Europay, Mastercard, and Visa transactions.

NCCIC encourages users and administrators to use the following best practices to strengthen the security posture of their organization’s systems:

- Maintain up-to-date antivirus signatures and engines.

- Keep operating system patches up-to-date.

- Disable file and printer sharing services. If these services are required, use strong passwords or Active Directory authentication.

- Restrict users’ ability (i.e., permissions) to install and run unwanted software applications. Do not add users to the local administrators group unless required.

- Enforce a strong password policy and require regular password changes.

- Exercise caution when opening email attachments, even if the attachment is expected and the sender appears to be known.

- Enable a personal firewall on organization workstations, and configure it to deny unsolicited connection requests.

- Disable unnecessary services on organization workstations and servers.

- Scan for and remove suspicious email attachments; ensure the scanned attachment is its “true file type” (i.e., the extension matches the file header).

- Monitor users’ web browsing habits; restrict access to sites with content that could pose cybersecurity risks.

- Exercise caution when using removable media (e.g., USB thumb drives, external drives, CDs).

- Scan all software downloaded from the internet before executing.

- Maintain situational awareness of the latest cybersecurity threats.

- Implement appropriate ACLs.

For additional information on malware incident prevention and handling, see the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Special Publication (SP) 800-83: Guide to Malware Incident Prevention and Handling for Desktops and Laptops.[2]

Response to Unauthorized Network Access

Contact DHS or your local FBI office immediately. To report an intrusion and request resources for incident response or technical assistance, contact NCCIC at ([email protected] or 888-282-0870), FBI through a local field office, or the FBI’s Cyber Division ([email protected] or 855-292-3937).

References

- [1] Symantec: FASTCash: How the Lazarus Group is Emptying Millions from ATMs

- [2] NIST SP 800-83: Guide to Malware Incident Prevention and Handling for Desktops and Laptops

- October 2, 2018: Initial version

- December 21, 2018: Added link to Symantec blog

This product is provided subject to this Notification and this Privacy & Use policy.

Continue reading...